|

Where to start? The

Chicken or the Egg- the Revolver or the Cartridge? Both the Old Colt

revolver and the .32 S&W Long cartridge have played

important roles in handgun history but are largely ignored by

the popular press. Nevertheless,

they have a cadre of dedicated enthusiasts and become the

subjects of frequent discussion on the Internet boards.

What I have been

shooting is a Colt Police Positive Special - a revolver in

production from 1908 until the late 1970s.

Its antecedents include the Colt New Police of 1896, the

Pocket Positive and the short cylinder Police Positive of 1905.

Its progeny includes the Detective Special and the target

sighted Diamondbacks - sporting revolvers much valued by

collectors and connoisseurs.

It is built on the small .38 platform that, in latter

years, became known as the “D” Frame. All of these revolvers

employ the 1905 vintage “Positive Safety”, a hammer-block

that permits safe carry with all chambers loaded.

It is the most –produced revolver in the Colt line,

encompassing some 750,000 units with room for confusion

occasioned by shared serial numbers.

The

designation “Special” Comes from the lengthened cylinder

which allowed it to house its most popular cartridge - the .38

Special / Colt New Police and incidentally, the 32-20 WCF

cartridge.

What

makes my particular example “Special” is that it is

chambered for the .32 Colt New Police Cartridge.

This is the politically correct name for the .32 Smith

and Wesson Long when chambered in a Colt. Colt did this -

both with the .32 and the .38 Special - named them the “Colt

New Police” to avoid advertising the Smith and Wesson

developments. The Police Positive Special will fire the old .32

S&W cartridge as well as the Long and will not do at all

well with the old .32 Colt and Long Colt Cartridges.

These rounds use the same nominal .312-313 bullet that

are of the full case diameter, heeled variety like the modern

.22 rimfires. Firing

them in 32 S&W Long chambers will over expand the smaller

cases ripping them from Dan to Beersheba in the process.

The .32 S&W and S&W Long cases are too large to

fit in the older Long Colt chambers. This is a good thing.

Another special aspect

of the revolver on hand is its production vintage of 1949-50. It

is a mechanically pristine example of mid-century craftsmanship

and engineering. Its

smooth action, well defined sights and light trigger combined

with a 4” barrel go far toward reducing (but not eliminating)

the difficulty I have in hitting things with small,

pocket-portable revolvers. The features make for pleasurable

casual shooting at moderate ranges. The double action stacks and

feels strange to the shooter used to a Smith and Wesson, but

this revolver proves very accurate in that mode - reliably

bouncing cans out to fifty feet or so.

The

.32 Smith and Wesson Cartridge dates from the late 1870s and was

a ubiquitous presence in the various single and double action

pocket pistols manufactured up until World War II.

The Long variation came along in 1896 with the

introduction of Smith and Wesson’s first hand ejector

revolver. It

received a jump-start as a police cartridge when Commissioner Theodore

Roosevelt acquired the Colt New Police revolver as the

standard arm for the New York City Police Department.

Roosevelt was deeply impressed by the extremely poor

marksmanship of the NYC officers and it seems likely that he

chose the .32 for its light recoil rather than any great regard

for the small bore as Man-Stopper.

Whatever the reasoning, the Colt and Smith .32 Longs were

quickly adopted by several northeastern police agencies and the

cartridge remained a police standard for some time to come.

The round proved very accurate and gained worldwide

acceptance as a target cartridge.

Colt, Smith and Wesson, Charter Arms, Taurus and

others produced substantial numbers of .32 S&W Long /Colt

New Police revolvers right up until the development of the .32

H&R Magnum Cartridge.

In the late 1960s, Dean Grennell experimented with

uploaded rounds in his K 32 while promoting development of a .32

Magnum as a small game cartridge - an event that didn’t take

place until about 20 years later.

In the 60s, handbook entries carried 100- grain bullet

loads up to the 1,000fps mark and into the low-magnum

performance range.

In

the present day, there is a general dearth of truly small-framed

.32 Magnum revolvers and the old quality Colts and small-framed

Smiths continue to cause considerable excitement among handgun

enthusiasts. Even those who like the little revolvers frequently regard it

as a novelty and disparage the .32 Long as a practical round.

Several factors combine however, to give the cartridge an

excuse for being:

-

The

.32 Long Cartridge loaded with fast-burning powder delivers

more on-target energy than the .22 rimfire rounds regardless

of barrel length;

-

The

.32 generally performs more efficiently from the

oft-encountered 3-4” barrels than do the .22 Long Rifle or

Magnum rounds delivering less round to round variation and

often exhibits better accuracy;

-

The .32 Long is

different enough to be different - an important

consideration whenever you get tired of everything being the

same.

My

exploration of the Colt Police Positive Special in .32 Long is

informed by several realities.

On the positive side is the abundance and variety of

reloading components suitable to the cartridge. On the negative

vector, are my personal limitations in regards to actually

hitting anything with a small framed, short barrel revolver. I

address the latter by limiting my expectations to a realistic

practical range for shooting such things as small game and other

targets of opportunity. This would seem to be about 50 feet.

The former factor - the availability of suitable

reloading components - comes into play as I develop loads that

hit reasonably close to the fixed sights at the 50 foot

distance. These loads must group suitably well to dispatch

something the size of a cottontail rabbit.

The

.32 S&W factory loads were accurate enough for government

work but hit several inches low. The same was true of the not-very-accurate Aguilla .32

Long 98-Grain Round Nose. The

PMC version of the same load grouped very well from a

casual field rest at 50 feet and hit an inch or a bit more under

point of aim. Unlike the Aquilla load, the PMC fodder ignited

reliably with no misfires.

I quickly learned that 90-100 grain bullets driven to

slightly over 800 fps would consistently group well under 2”

and hit usefully close to the sights.

The Lyman 3118 115-grain bullet designed for the

32-20 grouped about 1.5” and hit point of aim loaded to just

over 700 fps. I

obtained excellent results from the 100 Meister cast

double-ended wadcutters loaded to 800 fps and got a very decent

1” group from the Hornady HBWC from about 25 yards.

Loading

hollow-based wadcutters reversed often produces profound

expansion in .38 Special revolvers. In .32 and .32 Magnum both the Speer and Hornady

bullets tumble badly when loaded in this manner.

In

a small case like the .32 Long, minor changes in components,

powder charges and loading procedures make a big difference over

the chronograph. Fast-burning

powders clearly show the most consistent velocities. Bullets

that take up a large portion of the case,

like the wadcutters or the long-shank 90-grain

semi-wadcutter from Hornady, likewise produce small shot to shot

velocity variations. It is not particularly hard to produce good, accurate hand

loads in this caliber but the importance of minor variables make

it hard to depend upon published loading data for a reliable

prediction of what your home concocted loads will actually do.

In

my own case, I found that there would not be any particular

advantage in straying from Alliant Bullseye and the

wadcutter bullets from Meister and Hornady.

I’ve

used these bullets loaded to the 800 fps range in both .32

S&W Long and .32 Magnum and find that they are efficient

collectors of game. I’ve validated this by collecting a few

cottontails, a couple of jackrabbits, and one galloping

armadillo. I suspect that some stopping power enthusiasts will

pronounce the wide, flat aspect of the .32 wadcutter a more

efficient “man-stopper!” than the .38 Special RNL. Wild

guesses of this sort are unlikely to be refuted by any extensive

real-world database.

Given

suitable load selection, this Colt Police Positive Special

provides a practical alternative to the rimfire “Kit Gun.”

It provides an interesting foray into a little-chronicled

chapter of handgun history.

Meister

Cast Bullets are available from Dillon

Precision and online at http://www.meisterbullets.com/.

Mike

Cumpston

NOTE: All load data posted on this

web site are for educational purposes only. Neither the author nor

GunBlast.com assume any responsibility for the use or misuse of this data.

The data indicated were arrived at using specialized equipment under

conditions not necessarily comparable to those encountered by the

potential user of this data. Always use data from respected loading

manuals and begin working up loads at least 10% below the loads indicated

in the source manual.

Got something to say about this article? Want to agree (or

disagree) with it? Click the following link to go to the GUNBlast Feedback Page.

All content © 2004 GunBlast.com.

All rights reserved. |

|

Click pictures for a larger version.

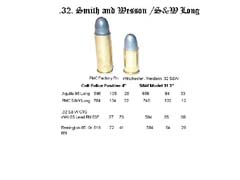

.32

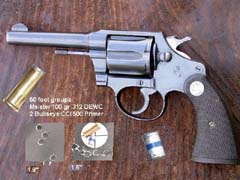

Colt Police Positive Special

The PMC factory 98-grain round nose at 50 feet from a

seated field position.

.32 S&W, 50 feet seated, using knees for a rest.

Comparison of .32 Smith and Wesson and .32 S&W Long.

.32 S&W Long / Colt New Police handloads.

50-foot groups, Meister 100-grain .312 DEWC over 2

grains of Bullseye with CCI 500 primer.

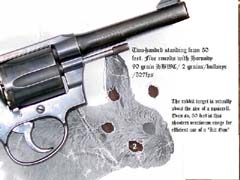

Two-handed standing from 50 feet, five rounds with

Hornady 90-grain HBWC over 2 grains of Bullseye (827 fps).

Lyman cast 115-grain .32-20 bullet at 50 feet.

|

![]()